Uncle Dr Terry LeBlanc: ‘Native perspectives on Land and Place’

We are all related. Connected together. We touch one another with life lived on the land together. Interrelated and interdependent with the land.

NAIITS stands for North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies, partnering to become an indigenous learning community here at Whitley.

The land is not to be feared or conquered but is part of us. Adam (adamah – earth) red dust on the ground. We are dust. We are the same dust.

THEOLOGY OF LAND

The Great Divide

- Dualism: dividing the spiritual from the material

- The reformers also divide the spiritual from the material: spiritual and political are now separated. Political and land separated.

Invited to do a welcome to Christian and Muslim refugees in Canada and was able to say: As I’ve welcomed the 500 years of refugees represented behind me I also want to welcome you. I’m sorry you’ve had to flee violence, to lose connection to the land of your ancestors.

Place – security, growth, wonder, sights smells… experience what God has for us in this place.

Utilitarian View of Land

- Commodification of land the breaking loose of land from people along with the loss of work – labour now becomes a commodity.

- John Locke and the primacy of private ownership.

- Nature is seen as an enemy to be subdued and dominated.

Colonisers saw indigenous people as godless heathen savages. We can do this to Muslims still – see them as godless people of a godless land but this isn’t truth. This belies a faith that says God is everywhere and all are made in the image of God.

Uncle Rev Ray Minniecon: ‘Walking the Land’

How as people and pastors can we operate to be authentically indigenous and authentically Christian? I ask myself these questions:

- Who am I?

- Where have I been?

- What do I do?

We are always in search of our people. We meet and tell our stories. Sometimes our great, great, grandparents lived at the same mission. Did they have other brothers and sisters? We don’t always know. People from a different family, from a different mob, from a different country might hold part of our story that hasn’t been heard.

I am confronted by racism everyday. I have learned how to have faith and to draw on the strength of the ancestors… ‘so that your faith might rest not on human wisdom but on the power of God’. (1 Cor 2:5). This includes church who continue to exclude us. I’m invited to speak about aboriginal issues but not to preach the gospel. That is why I started a little congregation in community at St John’s Anglican in Glebe called ‘Scarred Tree Indigenous Ministries‘. We are grateful to work on land that has the last Scar Tree in Sydney CBD. It is a way for us to connect to our history and to the gospel. we have to confront Australia’s history as a church, neighbourhood and community. we would lose our minds, selves, souls if we don’t stand up.

TALKING CIRCLES

Someone in our group shared their story adding, “when you don’t know who you are, there are no reference points.”

Psalm 68:5-6 (NIV)

5 A father to the fatherless, a defender of widows,

is God in his holy dwelling.

6 God sets the lonely in families,

he leads out the prisoners with singing

God as Father gave me a sense of who I am. Knowing this, no one is a mistake. Then I had a moment on country in a park with sunlight… I knew I belonged to the land and felt known. Mother (Nature) – living and breathing.

Aunty Rev Patricia Courtenay: ‘Aboriginal spirituality in an era of displacement’

IDENTITY

Where did I grow up? What country is that and what language is spoken there?

ASSIMILATION

- Displacement

- Denial of culture and spirituality

- Disconnection

RESPONSES

Our language is not ‘lost’, our home is not ‘lost’, we are disconnected from them.

Why would you want to identify as aboriginal?

I am supported, protected and reminded who I am by my ancestors and totem animals. My strength is in my spirituality.

How can you identify as Aboriginal and a Christian?

I can separate the faith of the missions from Christianity. There is a spiritual basis for this – acceptance of all – Jew and Gentile… 1 Cor 7:17-20. Live the life that the Lord has assigned… obey the commands of God in all things. You were provided identity at birth. Who were you called to be? Dualistic enquiry – I can be Christian without denying or giving up my cultural identity or heritage. Who I am is rooted in belonging and connectedness.

CULTURALLY SPIRITUAL WAYS OF KNOWING AND BEING

- sense of belonging: Aboriginal belonging comes from story and love of the land. Aboriginal people know and keep these stories. Are able to use these in other contexts. Able to use these for survival. We have an embedded spiritualness and awareness of sacred space.

- holistic worldview: spirituality and culture are invisible. Our mind and body’s wellbeing are interconnected with our spirituality. An attack on one affects the other areas.

- spirits of place: we have an oral tradition and literacy. We have a spiritual connection to the land and knowledge generation and re-generation. Supernatural and natural occupy the same place and time. Not mystical but mundane and embedded in the landscape. Someone might stay at a place and dream there – we learn through dreams. This is considered a geographic source of sacred knowledge. The revelation comes to the person in the right place at the right time. This is about identity, kinship and relationship to the land… receiving wisdom. This wisdom is omnipresent but non-visible for no-indigenous. Not mythfolk, lore or legend speaking of the past but continue happening now.

Aboriginal Australia still exists. When we gather and tell our stories ‘the land is speaking’. As guardians of the the land ‘we are speaking for the land’. The Creator Spirit/God’s relationship with indigenous people does and will continue to exist. Language, world views, etc. can be shared with those willing to listen.

CREATING AN AUSTRALIAN CHRISTIAN

- how do indigenous Australians reconnect culturally and spiritually?

- how do non-indigenous Australians relate to indigenous Christians culture and spirituality?

‘Know the past, change the future’

Aunty Rev Janet Turpie Johnstone: ‘Bunjil weaves past and future in the present’

Wominjeka – ‘we have come together for good purpose’

When we have shared stories and place, that goes with us when we leave.

Bunjil patterns the past and future in the present. We’re not Animist, we don’t worship animals but are related to them and to the river.

Can we live with the land and waters so that everything has a place to live?

- colonial invasion

- Bunjils narratives

- work with local elders eg. Bunjil’s Nest Project.

Reconciliation:

- multiculturalism

- migration

- recognise

- silence – denial

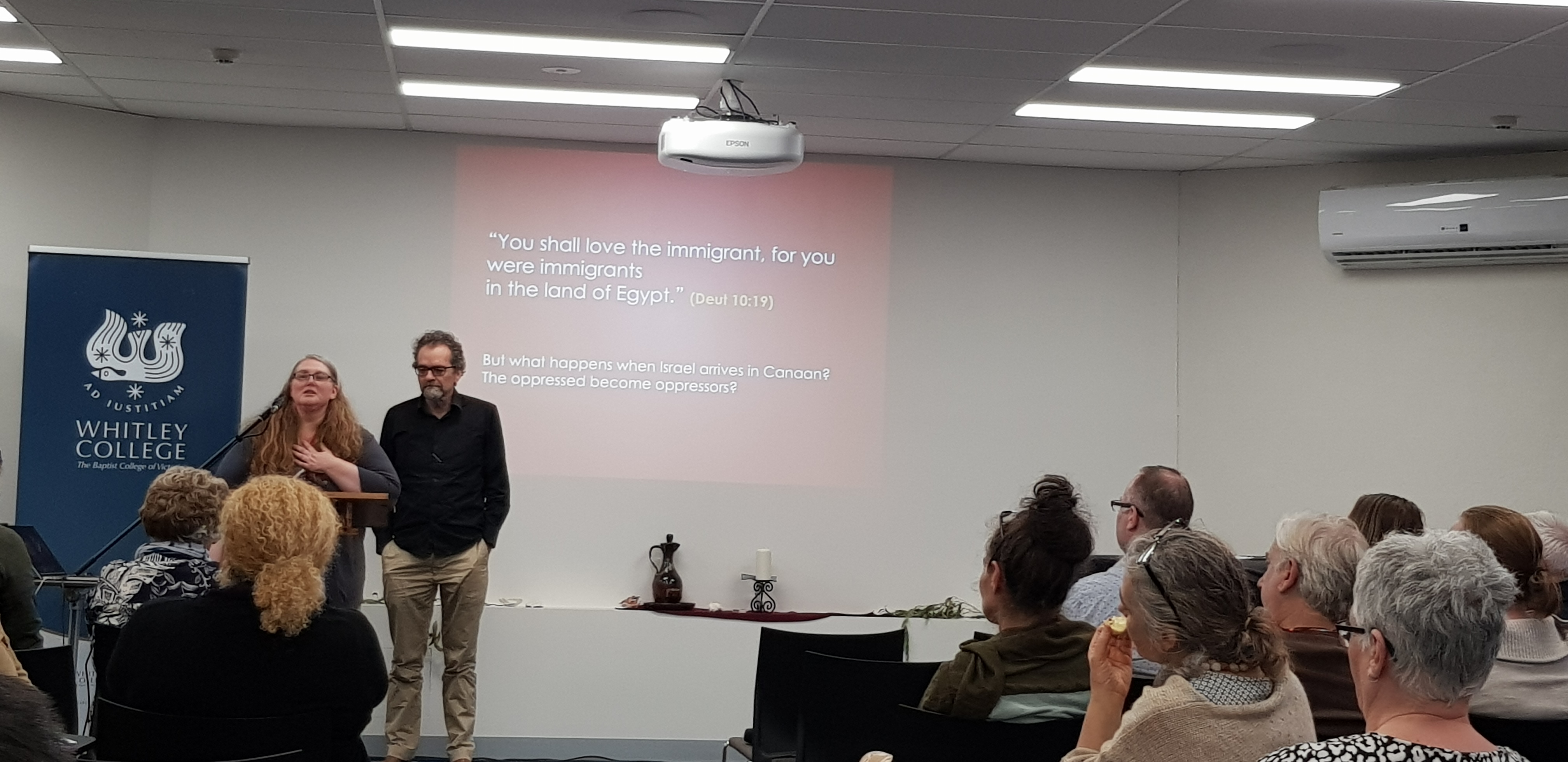

Professor Mark Brett & Naomi Wolfe: ‘Traditional Land and the Responsibility to Protect Immigrants: A Dialogue between Aboriginal Tradition and the Hebrew Bible’

“You shall love the immigrant, for you were immigrants in the land of Egypt” (Deut 10:19)

But what happens when Israel arrive sin Canaan? The oppressed become oppressors?

Indigenous mob don’t need a qualification to be who they are. But this partnership has arisen from an international journey and collaboration.

Strangers, immigrants, sojourners… it’s the story of people who took others’ land. If you don’t take care of the widow, orphans, migrants… you will lose your country.

Indigenous: country knows them, calls them home. There’s a kinship system and people are looked after. ‘no one should be left behind’

Jer 26: 8-9 and Jer 26:16-19 people hated what he had to say… except some elders. Not citing Deuteronomy but oral storytelling – there moral compass is somewhere else. In the Samaritan story, who do indigenous people see themselves as in the story? Where are the settlers in the story?

We’re all Gentiles. Settlers brought the thinking, they are the new Israel. They have the right to take the country. That’s wrong. They think they’re superior and that God is on their side. There is a theological problem with this logic. White people are not the new Israel.

There is an idea that our liberation is bound to native title, but that’s extinct in Tasmania. So what does freedom look like for those of use from there?

- where are we?

- what does that look like for our relationship with settlers

- what does that call us to be?

- how does it call us to live?

Reinterpreting our stories:

Every identity therefore is a construction… a composite of different histories, migrations, conquests, liberations and so on. We can deal with these either as worlds at war or as experiences to be reconciled. Edward Said.

What next?

- go back to the text

- what does that mean for me?

- Who am I? What’s my cultural identity?

- how do I engage gospel? … those around me?

Reading the Bible as Israel is toxic for Gentiles. Colonised people are colonising.

Our beliefs are already here, we don’t need yours. Our sacred land is right here. Our text is the land – we hear it with our feet and our hearts. It is broader and more inclusive.

We can have/give/build what was denied to earlier generations if we’re strong in culture.

Wonderful animation…

Bunjil The Creator: Bunjil’s Flight to the Stars