I went to an event this week that talked about racism and how most people make it to the level of “tolerance” but rarely make it to “acceptance”. Acceptance is the level where diversity is incorporated and celebrated. A panel was asked: “What signals that a space is safe?” And the answer is: “Evidence that you have done your own work on this.”

So, how a space is configured, it’s art and decorations might contribute to safe space but so too does language. Churches often talk about being spaces of “welcome” but in how many languages are you saying it? Do you express the multiculturalism of your community? Do you have it in Braille? Is it large print for the elderly? Colourful for the children? Indicate that those who are LGBTIQA+ are welcome?

I don’t necessarily mean literally having a welcome sign that incorporates all those things but holding space to learn from how someone with a Vietnamese or Sri Lankan cultural lens experiences God, what does the God who calls us to look and see, or hear and listen, mean to someone who is blind or deaf? What does faith in a triune God mean to someone with an extra chromosome? How does someone identifying as LGBTIQA+ who has been disavowed by their family relate to a Holy Father?

In no particular order, playfully explore language and liturgy now that invites you into another way of knowing, follow links for more…

THE LORD’S PRAYER: MAORI & POLYNESIA

Eternal Spirit,

Earth-maker, Pain bearer, Life-giver,

Source of all that is and that shall be,

Father and Mother of us all,

Loving God, in whom is heaven:

The hallowing of your name echo through the universe;

The way of your justice be followed by the peoples of the world;

Your heavenly will be done by all created beings;

Your commonwealth of peace and freedom

sustain our hope and come on earth.

With the bread we need for today, feed us.

In the hurts we absorb from one another, forgive us.

In times of temptation and test, strengthen us.

From trial too great to endure, spare us.

From the grip of all that is evil, free us.

For you reign in the glory of the power that is love,

now and forever. Amen.

The New Zealand Book of Prayer

ABORIGINAL LORD’S PRAYER

(there is a lovely sung version of this)

You are our Father, you live in heaven

We talk to you, Father, you are good

We believe your word Father, we are children,

Give us bread today

We have done wrong, we are sorry,

Help us Father, not to sin again

Others have done wrong to us and we are

sorry for them, Father today

Stop us from doing wrong, Father

Save us all from the evil one

You are our Father, you live in heaven

We talk to you, Father, you are good.

Easter to Pentecost

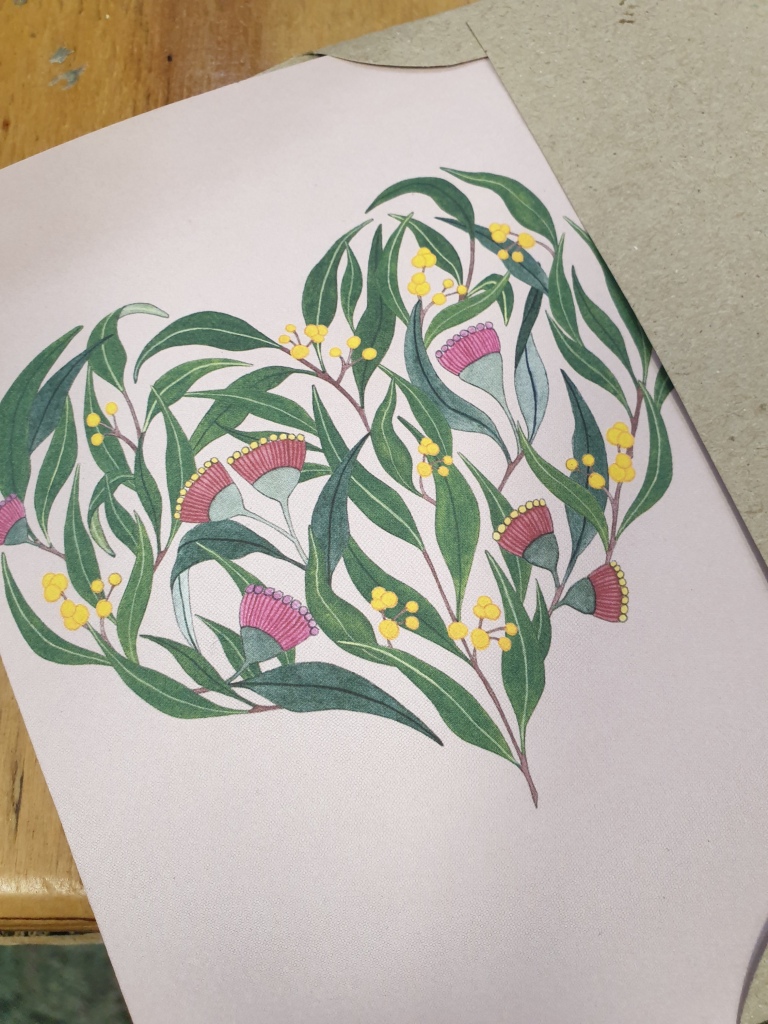

Wondrous God, lover of lion and lizard, cedar and cactus, raindrop and river, we praise You for the splendor of the world! We thank You, that woven throughout the tapestry of earth are the varied threads of human diversity. Created in Your image, we are of many colors and cultures, ages and classes, gender and sexual identities. Different and alike, we are Your beloved people. Free us, we pray, from fears of difference that divide and wound us. Move us to dismantle our attitudes and systems of prejudice. Renew our commitment to make this a household of faith for all people – gay, bisexual, lesbian, transgender, and straight – that all who worship and minister here may know the grace and challenge of faith. In our life together, grant us minds and hearts eager to learn, reluctant to judge, and responsive to the leading of Your loving Spirit. We ask in Christ’s name, Amen.

Alternative language for Psalms and Scripture…

Child Play by Joy Cowley

Father Mother God,

every now and then you call me

to drop my burdens at the side of the road

and play games with you.

I respond sluggishly.

Carrying burdens can make me feel important

and sometimes I’m afraid to drop them

in case I suddenly become invisible.

But when I do let go for a while,

how simple life seems –

and how beautiful!

God of play and playfulness,

thank you for castles in the sand,

for swings and slides and soap bubbles,

kaleidoscopes, rainbows,

and wind to fly kites.

Thank you for child-vision

of flowers and stones and water drops,

for child-listening to the universe

humming inside a seashell.

Thank you for showing me one again,

a creation filled with laughter

and the enjoyment of your presence.

An thank you, thank you,

dear Mother, Father God,

for the knowledge

of your enjoyment of me.

Aotearoa Psalms: Prayers of a New People by Joy Cowley

Laughing Bird Liturgical Resources – Australian scripture paraphrasing.

Mark 1: 4-11

John the baptiser showed up in the desert preaching to the people. He called them to be baptised, to completely turn their lives around and receive God’s forgiveness for their toxic ways. Everyone came flocking to John from Jerusalem and from all the rural districts of Judea. They owned up to their wrongdoing and were baptised by John in the Jordan River, promising to mend their ways.

John was dressed in rough clothes made of camel hair and animal skins. He lived on bush tucker – grasshoppers and wild honey. This was the guts of his message: “After me comes the One who is way out of my league – I wouldn’t even qualify to get down on my knees and lick his boots. I’m only baptising you with water, but he will baptise you with the Holy Spirit.”

During those days, Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptised by John in the Jordan. The moment he came up from the water, he saw the sky open up and the Spirit coming down like a diving kookaburra and taking hold of him. And a voice filled the air, saying, “You are my Son; the love of my life. You fill me with pride.”

©2001 Nathan Nettleton www.laughingbird.net

Dadirri – A Reflection By Miriam – Rose Ungunmerr- Baumann

NGANGIKURUNGKURR means ‘Deep Water Sounds’. Ngangikurungkurr is the name of

my tribe. The word can be broken up into three parts: Ngangi means word or sound, Kuri means water, and kurr means deep. So the name of my people means ‘the Deep Water Sounds’ or ‘Sounds of the Deep’. This talk is about tapping into that deep spring that is within us.

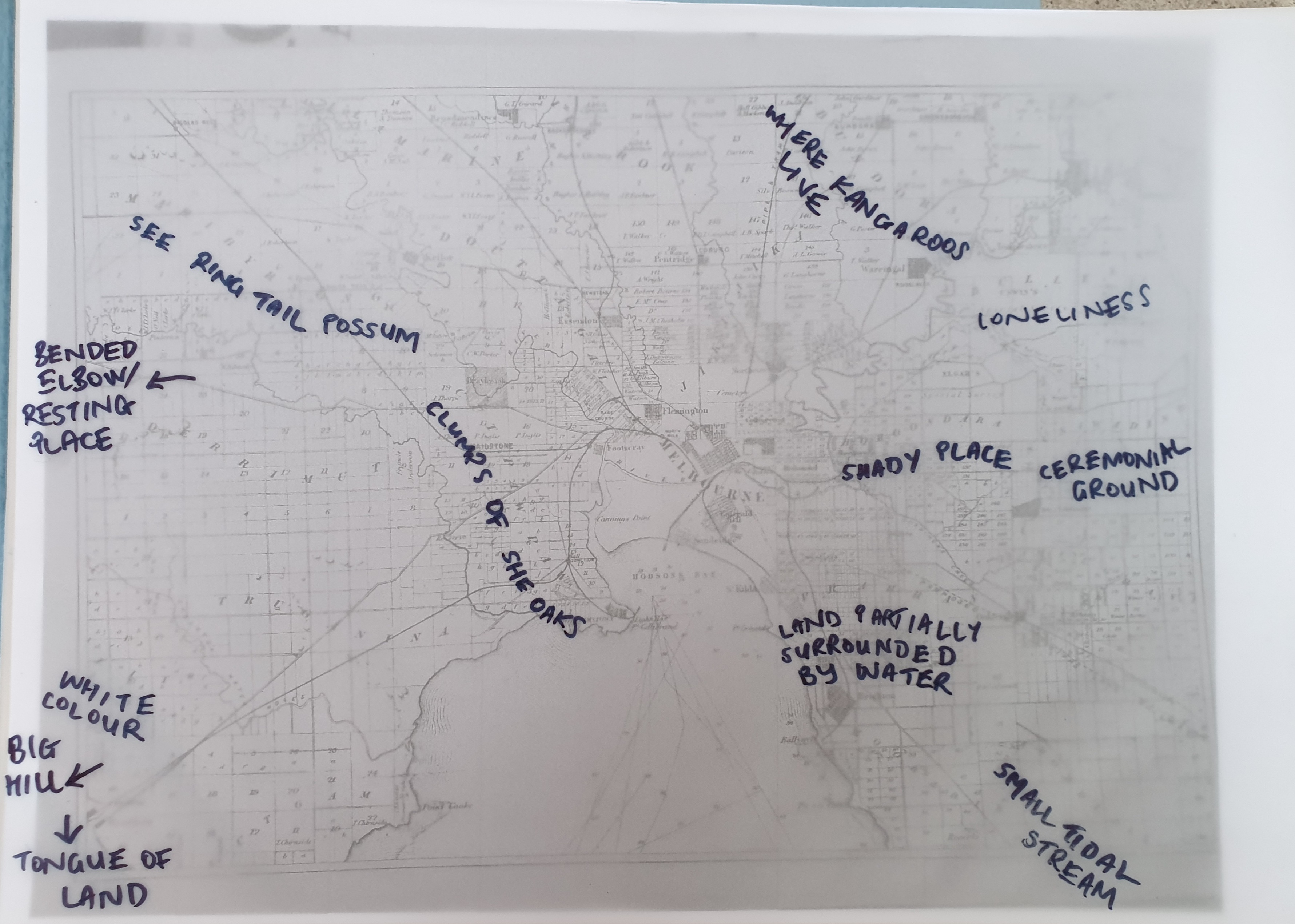

Many Australians understand that Aboriginal people have a special respect for Nature.

The identity we have with the land is sacred and unique. Many people are beginning to

understand this more. Also there are many Australians who appreciate that Aboriginal

people have a very strong sense of community. All persons matter. All of us belong. And

there are many more Australians now, who understand that we are a people who celebrate together.

What I want to talk about is another special quality of my people. I believe it is the most

important. It is our most unique gift. It is perhaps the greatest gift we can give to our

fellow Australians. In our language this quality is called dadirri. It is inner, deep listening

and quiet, still awareness. Dadirri recognises the deep spring that is inside us. We call on it and it calls to us. This is the gift that Australia is thirsting for. It is something like what you call “contemplation”.

When I experience dadirri, I am made whole again. I can sit on the riverbank or walk

through the trees; even if someone close to me has passed away, I can find my peace in

this silent awareness. There is no need of words. A big part of dadirri is listening.

Through the years, we have listened to our stories. They are told and sung, over and

over, as the seasons go by. Today we still gather around the campfires and together we

hear the sacred stories.

As we grow older, we ourselves become the storytellers. We pass on to the young ones

all they must know. The stories and songs sink quietly into our minds and we hold them

deep inside. In the ceremonies we celebrate the awareness of our lives as sacred.

The contemplative way of dadirri spreads over our whole life. It renews us and brings us

peace. It makes us feel whole again…

In our Aboriginal way, we learnt to listen from our earliest days. We could not live good

and useful lives unless we listened. This was the normal way for us to learn – not by

asking questions. We learnt by watching and listening, waiting and then acting. Our

people have passed on this way of listening for over 40,000 years…

There is no need to reflect too much and to do a lot of thinking. It is just being aware.

My people are not threatened by silence. They are completely at home in it. They have

lived for thousands of years with Nature’s quietness. My people today, recognise and

experience in this quietness, the great Life-Giving Spirit, the Father of us all. It is easy for

me to experience God’s presence. When I am out hunting, when I am in the bush,

among the trees, on a hill or by a billabong; these are the times when I can simply be in

God’s presence. My people have been so aware of Nature. It is natural that we will feel

close to the Creator.

Dr Stanner, the anthropologist who did much of his work among the Daly River tribes,

wrote this: “Aboriginal religion was probably one of the least material minded, and most

life-minded of any of which we have knowledge”…

And now I would like to talk about the other part of dadirri which is the quiet stillness and the waiting. Our Aboriginal culture has taught us to be still and to wait. We do not try to hurry things up. We let them follow their natural course – like the seasons. We watch the moon in each of its phases. We wait for the rain to fill our rivers and water the thirsty earth… When twilight comes, we prepare for the night. At dawn we rise with the sun. We watch the bush foods and wait for them to ripen before we gather them. We wait for our young people as they grow, stage by stage, through their initiation ceremonies. When a relation dies, we wait a long time with the sorrow. We own our grief and allow it to heal slowly.

We wait for the right time for our ceremonies and our meetings. The right people must

be present. Everything must be done in the proper way. Careful preparations must be

made. We don’t mind waiting, because we want things to be done with care. Sometimes

many hours will be spent on painting the body before an important ceremony.

We don’t like to hurry. There is nothing more important than what we are attending to.

There is nothing more urgent that we must hurry away for.

We wait on God, too. His time is the right time. We wait for him to make his Word clear

to us. We don’t worry. We know that in time and in the spirit of dadirri (that deep listening and quiet stillness) his way will be clear.

We are River people. We cannot hurry the river. We have to move with its current and

understand its ways.

We hope that the people of Australia will wait. Not so much waiting for us – to catch up –

but waiting with us, as we find our pace in this world.

There is much pain and struggle as we wait. The Holy Father understood this patient

struggle when he said to us:

“If you stay closely united, you are like a tree, standing in the middle of a bushfire

sweeping through the timber. The leaves are scorched and the tough bark is scarred

and burnt; but inside the tree the sap is still flowing, and under the ground the roots are

still strong. Like that tree, you have endured the flames, and you still have the power to

be reborn”.

My people are used to the struggle, and the long waiting. We still wait for the white

people to understand us better. We ourselves had to spend many years learning about

the white man’s ways. Some of the learning was forced; but in many cases people tried

hard over a long time, to learn the new ways.

We have learned to speak the white man’s language. We have listened to what he had

to say. This learning and listening should go both ways. We would like people in

Australia to take time to listen to us. We are hoping people will come closer. We keep on

longing for the things that we have always hoped for – respect and understanding…

To be still brings peace – and it brings understanding. When we are really still in the

bush, we concentrate. We are aware of the anthills and the turtles and the water lilies.

Our culture is different. We are asking our fellow Australians to take time to know us; to

be still and to listen to us…

Life is very hard for many of my people. Good and bad things came with the years of

contact – and with the years following. People often absorbed the bad things and not the

good. It was easier to do the bad things than to try a bit harder to achieve what we really

hoped for…

I would like to conclude…by saying again that there are deep springs within each of us.

Within this deep spring, which is the very Spirit of God, is a sound. The sound of Deep

calling to Deep. The sound is the word of God – Jesus.

Today, I am beginning to hear the Gospel at the very level of my identity. I am beginning

to feel the great need we have of Jesus – to protect and strengthen our identity; and to

make us whole and new again.

“The time for re-birth is now,” said the Holy Father to us. Jesus comes to fulfil, not to

destroy.

If our culture is alive and strong and respected, it will grow. It will not die.

And our spirit will not die.

And I believe that the spirit of dadirri that we have to offer will blossom and grow, not just within ourselves, but in our whole nation.

Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann is an artist, a tribal elder and Principal of St

Francis Xavier School, Nauiyu, Daly River, N.T.

© Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann. All Rights Reserved.

Experiencing Dadirri

Clear a little space as often as you can, to simply sit and look at and listen to the earth

and environment that surrounds you.

Focus on something specific, such as a bird, a blade of grass, a clump of soil,

cracked earth, a flower, bush or leaf, a cloud in the sky or a body of water (sea,

river, lake…) whatever you can see. Or just let something find you be it a leaf,

the sound of a bird, the feel of the breeze, the light on a tree trunk. No need to

try. Just wait a while and let something find you, let it spend time with you. Lie

on the earth, the grass, some place. Get to know that little place and let it get to

know you- your warmth, feel your pulse, hear your heart beat, know your

breathing, your spirit. Just relax and be there, enjoying the time together. Simply

be aware of your focus, allowing yourself to be still and silent…, to listen…

Following this quiet time there may be, on occasion, value in giving expression in some

way to the experience of this quiet, still listening. You may wish to talk about the

experience or journal, write poetry, draw, paint or sing…

This needs to be held in balance – the key to Dadirri is in simply being, rather than in outcomes and activity.

It’s also worth looking up Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr’s Stations of the Cross and the Aboriginal Eucharistic Liturgy.