[A short paper presented to the Spiritual Reading Group 21 July 2015 on Michael Leunig]

[A short paper presented to the Spiritual Reading Group 21 July 2015 on Michael Leunig]

So… Leunig… one of the questions he is most often asked and is always baffled by, is what does a particular cartoon mean? “People will say, ‘I don’t know what it means but I like it.’ Leunig replies… “I don’t know either but I like it too. I’m not trying to say anything but I hope it awakens something in you.”

Michael Leunig was raised listening to Oscar Wilde stories on the radio. He read Enid Blyton, Biggles and Childrens Encyclopaedias… he went to Sunday school and always said he found it, “not full of God but full of stories.” It was lyrical and what was lyrical made him happy – Leunig heard Psalms and asked of himself “What can I do like that?”

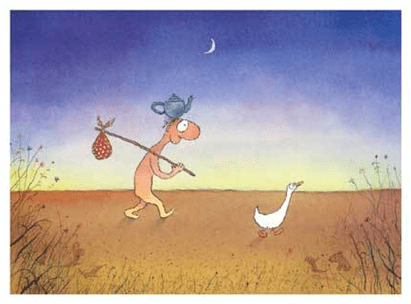

Though born in East Melbourne in 1945, Leunig grew up in Footscray going to Footscray North Primary School and Maribyrnong High School. Many of Leunigs friends, and many of his teachers when he grew up in the 1950s were war refugees or were the children of people from Germany, Russia, Poland. It was a very industrial area –ammunitions factory with machine guns firing, meat works, cannery… it smelt awful and drained into the river… for Leunig this wasn’t bleak but held lots of peace and space. Not a lot of nature around, but then you appreciate and give more significance to what you have… a duck and the moon.

A duck bought from the market while doing the family shop imprinted on Leunig following him around everywhere, coming home from school he’d turn the corner and the duck would see him and come running. So he always got ducks after that considering them playful and good-humoured and innocent with those rounded beaks.

A formative misadventure at eight years, occurred while playing at the rubbish tip Leunig stepped up to his thighs in hot coals and wires – receiving horrible and incredibly painful burns with fear of gangrene and amputation – for five months he couldn’t walk and had long periods of feeling cut off from others and lost.

From paper boy to making sausages at butchers on Barkley St, Leunig didn’t do well at school, repeating his last year, and came to work in the meatworks himself. This was great thinking time and Leunig advocates manual work that keeps your hands moving and your mind free. He said: “Working in such places either toughens or sensitises you” and it sensitised Leunig… he became a humanist (is now nearly vegan) and finely honed his earthy working class sense of humour. Leunig was conscripted for the Vietnam war in 1965 – he was going to fight it, a conscientious objector, but was rejected regardless when found to be deaf in one ear.

In Curly Stories, Leunig talks about it “Being an advantage to grow up without art consciousness… nothing to aspire to but things to find and create”. Homeschooling his own four children would have allowed him to foster a similar environment for them believing “Natural ideas exist within children… their play should be “utterly free” and they must be allowed to be bored – they feel free to explore and discover and the world is new to them and there’s this sense of wonder” Leunig refers to childrens ability to ‘blank out’ looking at a teapot spout or light through a window being present to what is right in front of them, commenting: “The loss of that beauty is appalling… how do I address that as a communicator? How can I express what everyone is feeling?” The prophet expresses the grief of the people. The artist expresses what is repressed.

Walking out of his 3rd year at Swinburne Film and Television School, it was 1969 when Leunig first began to work as a political cartoonist at Newsday, while the factories might have taught him to use humour – intellectual, witty, cynical – to deflect serious things, Leunig says “I was sung sentimental songs. Part of my first language. Fluent in that emotional language” His Grandma used to tell him: ‘All the world is bad, except for you and me, but even you’re a little strange.’ …perhaps this is where we meet The Creature… The Holy Fool– scribbled in the margins since school – amusing to his slightly hungover Editor, with a teapot on his head and riding a duck into the sunset, the image was put to print. Subhuman, primal, foetal, without gender. Leunig is somehow able to speak to our soul. To take small things and make them large, domestic things and make them sacred. For his own discipline he talks about the paradox of art theory – rules to follow, teachers to emulate >> how this stifles creativity. It’s about earning money, systematic success, built for efficiency, for velocity but you lose much, Leunig believes: “[You] cannot love or appreciate beauty at speed. How do you talk about it in ways that are unsuppressed and real? Might make a bridge with love, make a sandwich with love – it’s passed on to others. Love is what we go to bed thinking about.”

Walking out of his 3rd year at Swinburne Film and Television School, it was 1969 when Leunig first began to work as a political cartoonist at Newsday, while the factories might have taught him to use humour – intellectual, witty, cynical – to deflect serious things, Leunig says “I was sung sentimental songs. Part of my first language. Fluent in that emotional language” His Grandma used to tell him: ‘All the world is bad, except for you and me, but even you’re a little strange.’ …perhaps this is where we meet The Creature… The Holy Fool– scribbled in the margins since school – amusing to his slightly hungover Editor, with a teapot on his head and riding a duck into the sunset, the image was put to print. Subhuman, primal, foetal, without gender. Leunig is somehow able to speak to our soul. To take small things and make them large, domestic things and make them sacred. For his own discipline he talks about the paradox of art theory – rules to follow, teachers to emulate >> how this stifles creativity. It’s about earning money, systematic success, built for efficiency, for velocity but you lose much, Leunig believes: “[You] cannot love or appreciate beauty at speed. How do you talk about it in ways that are unsuppressed and real? Might make a bridge with love, make a sandwich with love – it’s passed on to others. Love is what we go to bed thinking about.”

Since his first book in 1974, Leunig has produced 23 more – books of newspaper columns, poetry and prayer in addition to his prints, paintings and drawings. Leunig shares intimacy with us, personal and confessional – e.g. The Kiss. We are invited into the privacy of his love life, his soul searching… Leunig makes the private public. He takes the small dark fearful things and brings them out where we can look at them “crying with the angels for a world that is different – this is not fatalistic but hopeful”. Perhaps it is because he has offered his own soul first that we are willing to listen to him expound on many themes:

>> loneliness >> the 9 to 5 grind >> war >> sex >> consumption >> love >> god >> media >> religion >> politics

It was being asked to contribute a cartoon to a new paper in 1989, The Age, that Leunig started writing prayers to the horror of his friends… Rather than born-again Christian Leunig’s interpretation lay in the realm of John Keats’s “negative capability”, a word for the unsayable and profound in life. He wanted to say the words publicly as another way of addressing the problems of our time, of our society, of our psyche, of people’s personal suffering {1998} His friends reactions sort of egged Leunig on, wanting to see how much he could push believing that “until a man discovers his emotional life and his gentle, vulnerable side, until he gives it expression, he never will find his women or his soul, and until he does find his soul he will be tortured and depressed and miserable underneath a fair bit of bullshit”.

From Archbishops to Presidents, the Opera House, Australian Chamber Orchestra, National Theatre in London to clay figure animations for SBS and remote communities in northern and central Australia – Leunig has Gone Places and Done Things. Declared a national living treasure by the National Trust in 1999 and awarded honorary degrees by 3 universities for his unique contribution to Australian culture.

The ‘war on terror’ following 9/11 was a watershed moment in Leunig’s cartooning work where, opposing the war and invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, he was at odds with many editors, commentators and members of Australian society – there became less gentle and lyrical themes and he stopped drawing the whimsical characters Mr Curly and Vasco Pyjama as often although the duck and the moon have still faithfully remained. Adding curls arose out of Leunig’s desire to communicate that “What makes you feel so alone and strange is in fact normal. There’s a lot of curliness in life and you can have a homecoming – there is a place for you and for that aloneness, that eccentricity, and there’s a fulfilment of it eventually, it’s no longer the cause of your outcastness. So that’s the curl. It’s the curious, unique self and, if you find that, you find the connection to the whole world because the world is curious and unique and authentic at its best level.” You might say the war, not understanding how people can fight other people this way, has been a breach to Leunigs sense of connection to Australian society and thereby rest of the world.

The ‘war on terror’ following 9/11 was a watershed moment in Leunig’s cartooning work where, opposing the war and invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, he was at odds with many editors, commentators and members of Australian society – there became less gentle and lyrical themes and he stopped drawing the whimsical characters Mr Curly and Vasco Pyjama as often although the duck and the moon have still faithfully remained. Adding curls arose out of Leunig’s desire to communicate that “What makes you feel so alone and strange is in fact normal. There’s a lot of curliness in life and you can have a homecoming – there is a place for you and for that aloneness, that eccentricity, and there’s a fulfilment of it eventually, it’s no longer the cause of your outcastness. So that’s the curl. It’s the curious, unique self and, if you find that, you find the connection to the whole world because the world is curious and unique and authentic at its best level.” You might say the war, not understanding how people can fight other people this way, has been a breach to Leunigs sense of connection to Australian society and thereby rest of the world.

These days, Michael Leunig has 3 small dogs but no ducks. He enjoys talking to strangers and going to bed at night. He is a devout nature lover and spends his time between the solitude of the bush in Northern Victoria and a home in Melbourne where he enjoys walking in the local park, morning coffee in the café, chamber music in the concert hall, and attending to work in his studio .

When asked: “What is the meaning of life?” Leunig replied: “For humans as for all the plants and creatures: know yourself, grow yourself, feel yourself, heal yourself, be yourself, express yourself”… “I want to be a voice of liberation”. Leunig speaks not only for the wealthy or the poor but both, not only those armed and those without weapons but both, not only the pretty people or only the ugly people but both – he enjoys this inconsistency and variety. As Barry Humphries says “through the vein of his compassion and humanity and his humour – illuminating many a darkling theme”

Like Jesus with his parables and questions – Leunig doesn’t present us with solutions or easy answers but an invitation. He sees his vocation as cracking what is stoic and cold in society – to make us feel anger, grief, joy, sadness… Leunig believes we have something to discover in the wrongness… “Live without ‘knowing’, in mystery. Find things. Unlearn. Get lost. Get primal, getinfantile. When you have lost all hope – start to play. You have nothing to lose. Stay with it and don’t take it too seriously…”

I hope maybe it awakens something in you.”

Indigenous stories tell something about a place and also about something happening there.

Indigenous stories tell something about a place and also about something happening there.